Josef Steiff and Tristan D. Tamplin, Ed. Anime and Philosophy. Chicago: Open Court, 2010.

Ada Palmer

It is a healthy sign that, as both the economy and the publishing industry shrink, books on anime and manga continue to proliferate. The design of a manga syllabus was once little more than a choice between Paul Gravett and Fred Schodt, but now we have genre-specific essay collections, fan culture studies, biographies, indexes, encyclopedias, journals, monographs and edited collections. This breadth makes it difficult to look with anything but scorn at the vast commercial franchises now milking the market: Manga for Dummies, The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Drawing Manga, The Rough Guide to Anime, and, particularly difficult, Anime and Philosophy, a contribution from the Open Court series which produced Baseball and Philosophy, Battlestar Galactica and Philosophy, even Transformers and Philosophy, all part of a profitable mass market series of fifty volumes and counting. Yet, wary as a scholar must be of the volume’s promise to include real philosophical content but minimize footnotes, such books do contribute to, while also certainly exploiting, the world of manga scholarship.

Anime and Philosophy provides thematically-organized chapters, mainly focused on the films and series best known to English-speaking audiences: Ghost in the Shell, Fullmetal Alchemist, Evangelion, Astro Boy, Gundam, Bleach, Dragonball Z, Totoro, Gunslinger Girl. The essays aim to connect these works to major Western thinkers, historical and contemporary. Some articles also treat Eastern concepts: Shinto, yin and yang, the cultural baggage of WWII — enough to awaken and guide the curiosity of those with the ambition to learn more. The volume is heavy on shōnen, sci-fi and cyberpunk, and repetitious citations may leave one with the impression that Haraway’s “A Cyborg Manifesto” is the most important work of literary criticism since Aristotle’s Poetics, but sections on heroes, devils and spirituality provide breadth. The absence of shōjo is striking. Christie Barber and Ean Dinello, who discuss cyborg gender, focus on Gunslinger Girl and Ghost in the Shell, and the only actual discussion of shōjo tropes is in Benjamin Chandler’s piece on Fullmetal Alchemist. The shōnen focus was the contributors’ choice, not the editors’, and editor Josef Steiff reportedly strove to recruit more shōjo content for the companion manga volume. Nevertheless, one must still question a book on anime and philosophy which does not once mention Sailor Moon or the yaoi genre.

The volume’s strongest elements are its multi-series treatments, including Andrew Terjesen’s piece on perfection in shōnen competition, Adam Barkman’s on Japanese pluralist approaches to Christianity, and Andrew Wells’ chapter on anxiety over humanity’s future evolution. Andrew A. Dowd’s piece on hentai and Alicia Gibson’s on Astro Boy and the nuclear age provide less novelty, but are good distillations of important discussions of which too many fans are unaware. Other chapters focus on single series. Some are successful, notably Daniel Haas on apocalyptic ethics in Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind and Cari Callis on Shinto in Spirited Away, while Benjamin Chandler addresses many interesting Japanese cultural questions in his close reading of Fullmetal Alchemist. Other chapters are weakened by narrow scope. In Louis Melancon’s treatment of ethics in Mobile Suit Gundam, discussions of the recent wars in Iraq feel incomplete without mention of Gundam Seed Destiny and Gundam 00, which both comment overtly on the Middle East crisis. Similarly, Ian M. Peters’ Aristotelian reading of Highlander: the Search for Vengeance includes no discussion of the questions of globalization or national identity involved in a Japanese adaptation of an American franchise about a Scottish hero set in a far future Rome built on the ruins of New York City.

Anime and Philosophy can be accused of Eurocentrism, since the essays dwell on Western influences, Heraclitus, Pascal and the Frankfurt School, without balancing them with equal discussions of the Kyoto School, Shinto, Buddhism, Zen and the other Asian underpinnings which mix with the Western in the undeniably international medium of anime. Yet this European focus is not necessarily a flaw given the volume’s goals and, especially, its target audience. American fans are not coming to this book for a lecture on Japanese culture, but to learn why they personally find their favorite shows so philosophically powerful. If a young fan from New York finds her understanding of gender transformed by Revolutionary Girl Utena, it is not as much because of its commentaries on Heian aesthetic morality or kabuki, bunraku and Takarazuka theater, but because it speaks to her own apparatus for understanding gender, derived largely from the Western gendered world in which she has been raised. The history behind that Western philosophical apparatus is consequently a valid analytic tool if the goal is to answer, not “What did the Japanese creator intend?” but “What philosophical connections am I as an American viewer experiencing as I watch?”

Anime and Philosophy is an introduction for fans who recognize that anime does not only make one laugh and cheer and cry but also think. It provides a discursive partner for those who have already begun to analyze these series on their own, and direction for those who want to know what names and keywords to look for as they pursue in libraries and journals the questions that proved so stimulating in animation.

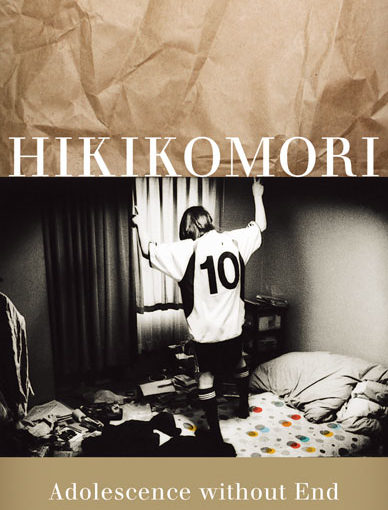

Is Anime and Philosophy a worthwhile book? If I am able to answer “yes,” it is not in my role as a scholar but as a teacher, one frequently approached by parents concerned that their children are getting into “this anime thing.” Concern is natural. Anime is an alien world to many, and as its fandom spreads in the Anglophone world, it has many of the earmarks of a subculture like the punk or hippie movements, with its own conventions, communities, fashions, even its “fan Japanese” dialect. In our era of ever-increasing commercialization, globalization and internationalization, I point out to parents that their teens will inevitably be into something alien; better that it be something which encourages study of a foreign language, culture and history. If upwards of 80% of students in Japanese classrooms today are drawn there by anime, how many schools would have lost their Japanese programs without it? It is possible if not common for an interest in anime to end with a DVD shelf and a Playstation, but frequently fan activities lead to the acquisition of valuable life skills. A serious cosplayer practices not only costume construction but organization, and budgeting; a fan-art booth in a convention Artist’s Alley requires entrepreneurship and graphic design; a fan fiction project involves creative writing and thinking, even peer review. Even a blog entry about the philosophy of Dragonball Z is one more philosophical exercise than many young people otherwise undertake, and therein lies the utility of Anime and Philosophy. The majority of students today, even in universities, are not only afraid of footnotes but confident that a research paper begins with a Wikipedia page and ends with its links section. Wikipedia does not link Astro Boy to Heidegger. This volume does.

Herbert Marcuse, discussing the one-dimensionality of modern society, notes that as the market commercializes countercultural trends, the protest album and Che Guavara T-shirt cease to have any meaning as forms of resistance. One may use Marcuse’s analytic tools without sharing his pessimism. He observes that too often subcultures that could be havens for alternative ideas are absorbed into toothless compatibility with the system they originally intended to resist. Anime fandom is no exception. It remains a capitalist enterprise, and the Popular Culture and Philosophy seriesis out to snare the young fan’s leisure budget as much as is Gundam. However, the quest for profit does not prevent either franchise from stimulating real thought, and for Western fans, providing real intellectual alternatives. The Shinto spirits of a Miyazaki movie may register to an American viewer as one more cache of anthropomorphized Disney animals, or they may introduce an alternate vocabulary for thinking about religion, nature and environmentalism. I believe anime scholarship benefits from having a supply of introductory guides to facilitate the transition from passive watching to active thinking. Such volumes introduce important names and terms, suggest further viewing and reading, and help curious newcomers, especially nervous parents. Because of the idiosyncratic nature of Western anime fandom, Anime and Philosophy will be valuable if it can succeed in adding literary analysis to the set of skills like graphics layout and entrepreneurship which fan passion leads many young otaku to acquire. Smart money still says that an Anime Convention panel on “The Philosophy of Fullmetal Alchemist” will not be worth the scholar’s time except as an anthropological study, and the same remains true of Anime and Philosophy. Academics already engaged in contemporary questions of cyborg identity and posthumanism will find little new. But for a lay audience it serves its purpose: to introduce the basic terms and questions, and so help fan curiosity become active analysis. If this type of book leads teens from Pluto and Naruto to Plato and Nichiren, that is a good thing.